Scenery Magazine - Private Lives

Photography by Nikolai von Bismarck. Words by Wilfred Lewis.

The skill of a good designer is often found in creating a space greater than the sum of its parts. But there is an equal skill – less recognised, perhaps, and certainly less widely practised in our time - in taking rare treasures and making from them a home that feels warm, comfortable, and alive.

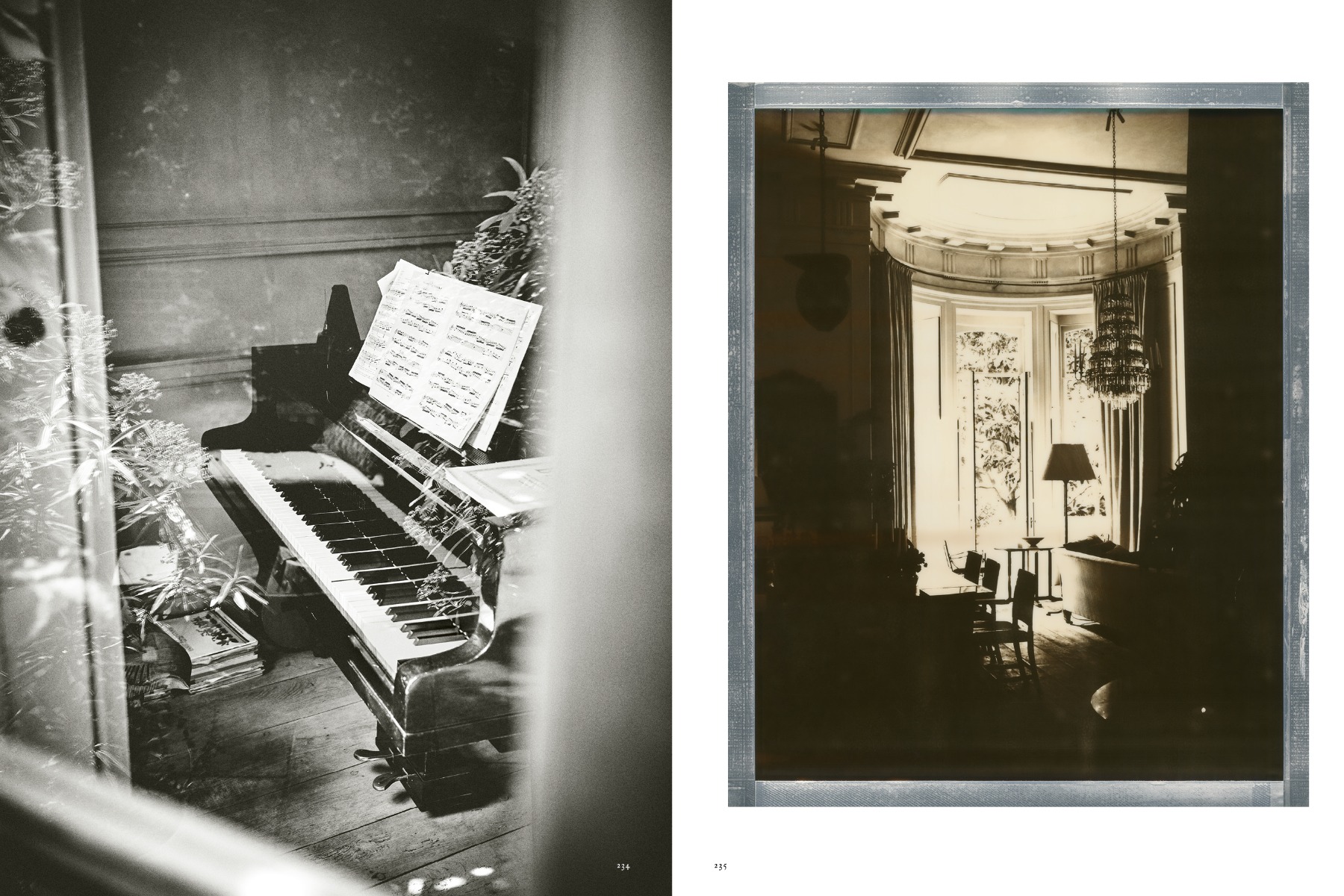

Rose Uniacke’s London home is such a place. Here, important pieces of furniture, art, and design, chosen with great discernment, come together to form an atmosphere so relaxed as to render each component invisible. This is not to say that the pieces do not sing – undoubtedly, they do – but rather to remark on the relaxed air of the space as a whole. Not a museum. Not too precious.

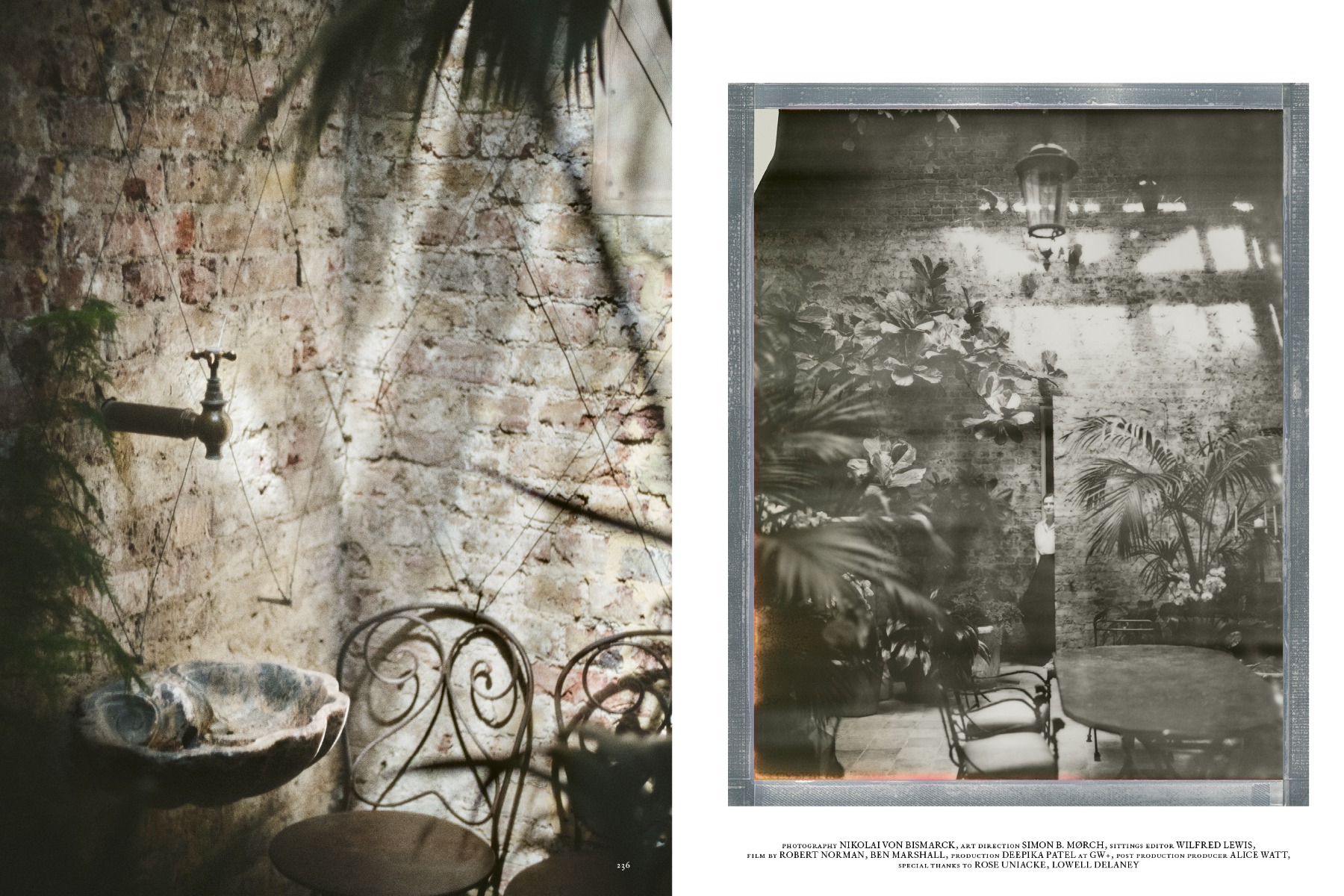

The Uniacke family home squats in the corner of a Pimlico garden square. It’s an oddity of a building: composing wide and awkwardly shaped walls of brick, tarnished with soot from the nearby railway lines which converge on the terminus at Victoria, and windows too large in scale and few in number. Built as a studio for the Scottish society portraitist James Rannie Swinton, the property served as his workplace, gallery, and residence, with rooms specially conceived for each purpose. The story of how Uniacke and her husband, the film producer David Heyman, came to acquire the house – and of their subsequent restoration of its interiors – has been told many times. So, suffice to say that a duo with less taste, bravery, and resolve would have faltered, such was the extent of intervention required.

There are photographs of the house from 1973 that document its previous life as an art school. One shows the impressive octagonal ballroom on the first floor laid out as an office – a Formica desk laden with papers and a full ashtray sits in the exact position that a William IV Oak partners desk now rests, and from where Uniacke conducts much of her daily business. Stepping into this room, those strangely angled walls and large windows suddenly carry purpose. Framing classic London views of terrace houses, a stone-built church, and billowing plane trees, cool light streams in past yellow silk taffeta curtains and casts across the many precious things that now call this room home. “By treating it lightly I found that I could let the spirit of the house speak, rather than its scale,” Uniacke says.

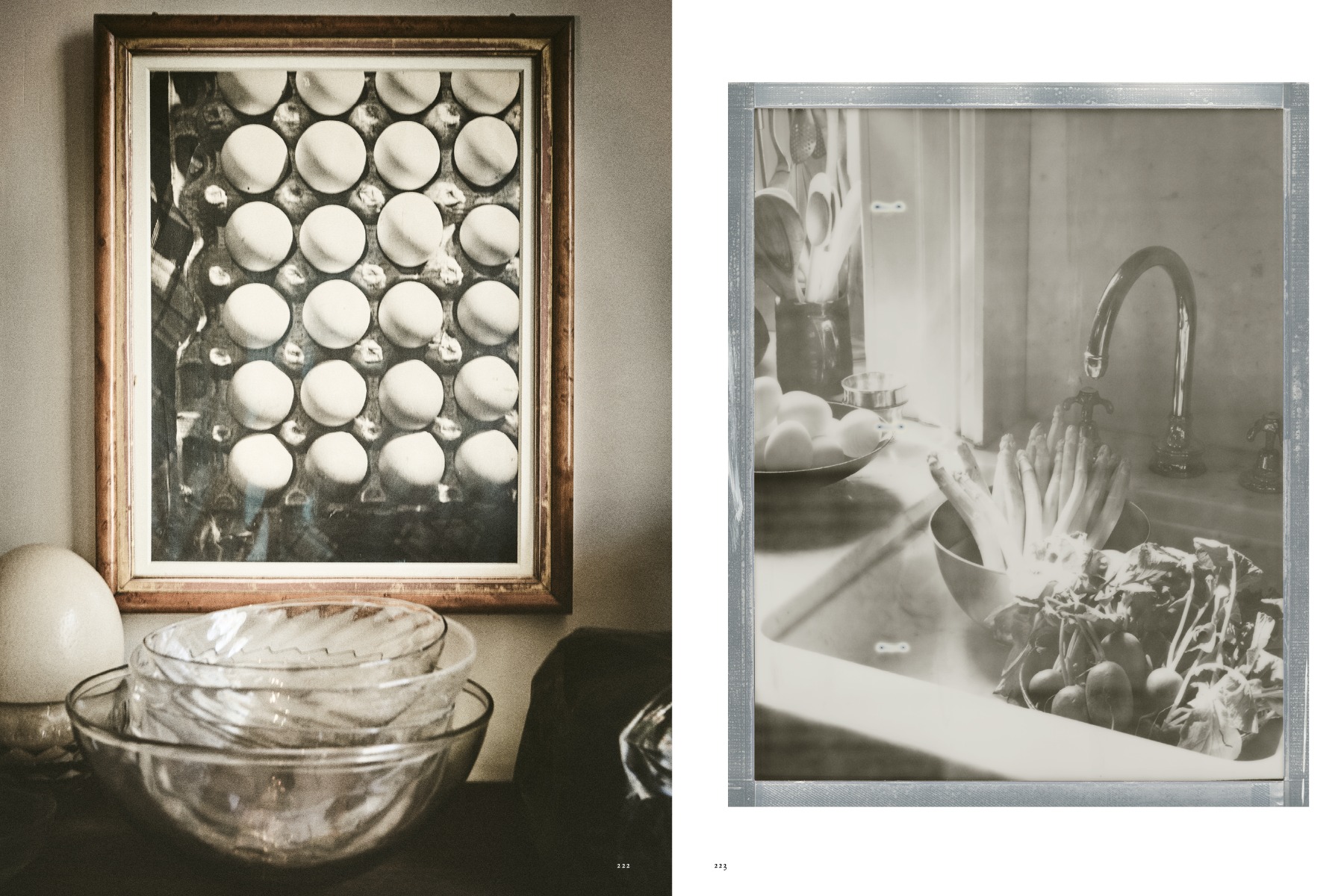

Uniacke’s collection, devised over a lifetime spent as a furniture restorer, antiques dealer, and more recently an interior designer of the highest repute, has been assembled with a throughline of erudition and taste that ties together what could otherwise feel disparate. We see an ancient Cycladic stone fragment sitting alongside a sculptural Spade vase by the 20th-century British ceramicist Hans Coper, in front of an artwork so contemporary the paint could still be wet. “Looking at things in relation to others is profoundly important to me,” she tells me on a recent spring morning at the house. “Seeing influences made stark and how one object can be enhanced by another.”

In the drawing room, where tall French windows lead onto a courtyard garden, there is a long refectory table which Uniacke refers to as the “landing place” – a space for new acquisitions to acclimatise “before they’ve found where they will live.” It’s evident, however, that no single piece or assemblage is set in aspic; the objects in this house are parts in an ever-changing set that alters according to the needs and fancies of their owner. The inevitable addition of everyday things – a VR headset propped against a Poul Henningsen lamp, or the neverfar - away pad of a dog’s paws – add a deliciously human touch.

Talking with Uniacke, it’s striking how often she returns to the idea of a room’s use, and how it should never be inflexible or inert. This was a lesson learned young from her mother, the antiques dealer Hilary Batstone, and the stylish homes in which Uniacke grew up. “There was always open space. I loved that space and felt free in it.” There is an energy to this house that belies its monastic reputation – a tangible hum of people and things in motion. When I visited in May, pea soup sat cooking on the stove, pieces were coming and going from a trial in a client’s house, and boasts of an enviable Wordle score echoed down the stairs. Here, Uniacke established what she always desired: a creative space where her family can live well, in comfort, and without ostentation.

Hidden away on a rooftop terrace is an outdoor shower with views of Westminster Abbey in one direction and Battersea Power Station in the other. The sleeve of a calypso record leaning up in Uniacke’s study reads: “London is the place for me” – and for Uniacke, it has been. This house, rooted in the city, has seen children grow up, careers blossom, and new faces arrive as the family has filled out.

But as we speak, Uniacke is beginning to conceive her next adventure: a new home. Having recently reacquired her parent’s clifftop cottage in Dorset, which was sold some 40 years ago, there are plans afoot for a small and simple one-bedroom dwelling. A very different kind of house, to be sure. But under the care of Rose Uniacke, it is likely to be no less beautiful a vessel for living than the one pictured here.